Iranian New Wave, Especially “Qeysar”

İlker Mutlu

Qeysar / Gheisar

Director & Scriptwriter: Masud Kimiai

Cinematographer: Maziar Partow

Soundtrack: Esfandiar Monfaredzadeh

Cast: Behrouz Vossoughi, Pouri Baneai, Naser Malek Motiee, Jamshid Mashayekhi

1969/100’/Iran

Qeysar! Where are you? They are killing your brother!

At first, this is a quotation which seems funny, isn’t it? However, this line passes in one of the most vital scenes of the film in which Qeysar’s brother Farman calls him in pain while he was being killed.

In my article celebrating the 50th anniversary of Samurai Rebellion (Masaki Kobayashi, 1967) in the previous issue, I also mentioned that the film I addressed was one of the most important productions of the Japanese New Wave. The years including 50s and 60s had “waved” cinemas of many countries. French, British, Czech, and Argentine New Wave movements broke out one after another. While the world was changing, it was not possible for cinemas of other countries not to be affected.

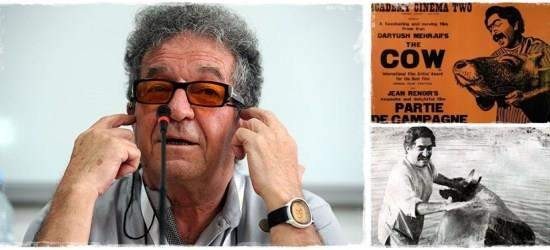

Likewise, Iran was to be affected before long. Iran’s movement started in 1969 with Dariush Mehrjui’s film called The Cow (Gāv) and continued with Masud Kimiai’s film Qeysar which was shot in the same year. With their new cultural and intellectual contents, the following films has changed the status of Iranian audiences and improved the quality of the productions. Dozens of high-quality films produced caused Iranian New Wave to get this name. Important directors including Forough Farrokhzad, Bahram Beizai, and Parviz Kimiavi were also the pioneers of this movement. Their films were innovative, poetic, and philosophical. Many directors like Abbas Kiarostami, Jafar Panahi, Majid Majidi, Mohsen, and Samira Makhmalbaf who are making the locomotive movies of today’s art films owe a great deal to these pioneers.

Dariush Mehrjui – The Cow (1969)

We can’t separate the rise of Iranian New Wave from those in other countries. The intellectual and political movements of the period were rapidly spreading all around the world. In Iran, after the coup in 1953, sociological approach gained importance in art, particularly in literature and reached the peak in 1960s. Thus, it was inevitable for this course not to affect the cinema.

In our previous issues, during the interview we did with Iranian Azerbaijani director Farid Mirkhani, we had discussed the development of Iranian Cinema. Therefore, I find it unnecessary to summarize the period before 1960 here. Although not being included in the New Wave, Ferruh Gaffari’s film In the South of the City (Jonubeshahr, 1958), which was censored and had its negatives burned, is one of the primary films that triggered the movement. By all means, this production is regarded as one of the first examples of socialist-realist cinema. Again the same director made the film The Night of the Hunchback (Shabeghuzi) which laid the foundations of art cinema in the country in 1964. Later on, talented young directors supported within the Iranian television started the Free Cinema movement in 1969. Ideas put forward and experiments done by these talented directors initiated socially sensitive films which represent the examples of political cinema. Earlier, Feridun Rehnama’s film Sivayeş Der Taht-e Cemşid (1960) which was inspired from the story of Sıvayeş in Ferdowsi’s work Shahnameh was screened in Locarno and Trieste Film Festivals, and awarded with Jean Epstein Prize in Locarno. Besides, this film had become the second film screened in The French Museum of Cinema (Musée de la Cinémathèque) after Ferruh Gaffari’s The Night of the Hunchback. In 1961, Ebrahim Golestan’s film called A Fire (Yek Atash, 1961) was awarded with Golden Mercury and Lion of Saint Mark awards in Venice Film Festival. Also, world famous woman poet Forough Farrokhzad’s film known as The House is Black (Khanehsiah ast, 1962) was selected as the best documentary, winning an award for Iranian cinema, in Oberhausen International Short Film Festival in 1963.

Qeysar’s director Masud Kimiai was born in Teheran in 1941. The film, which we addressed, made him famous in an instant and allowed him to be remembered as the person who changed the destiny of Iranian cinema. This film caused another genre to be born in the Iranian cinema: the tragic action drama. Though just having a few years of experience in being an assistant director and receiving no academic education on cinema or theater, Kimiai suddenly became a historical figure of Iranian cinema. He learned directing by watching films and through his early acquaintance with cinema. He talks about the times when he had waited in front of the Tehran cinemas, listening to the noise coming from the film screenings, and with the help of his friends’ narratives who stepped out of the cinema he would try to visualize the film in his mind. Another vivid memory from his childhood is the paintings of Rostam and Ashkbous behind his father’s car with which he was carrying flour to bakeries. As the car moved, he would think of the paintings as they came alive and started moving, and while habitually following the car from behind, he would try to guess the end of the war in these paintings. He had a rough childhood. He was uptight and he often got into fights that ended up in a police station.

At last, the time came and Kimiai started directing his energy to the books. These books were especially about cinema. Inevitably, this situation led him to seek jobs in film studios, till he met with the director Samuel Khachikian. He took his first lessons about techniques in film making from Khachikian and started his film career in 1965 as his assistant. Kimiai who proved himself with his energy and efforts, and earned the trust of the producers, had written and directed his debut film Come Stranger (Baigane Biya) in 1968.

Kimiai’s second film, Qeysar is differentiated from other Iranian films not only with its innovatory structure (this structure might seem out-of-date to most of us today, but it is still intriguing) changing the course of Iranian cinema, but also with its way of handling women sexuality bravely. Moreover, he achieved this success only with his second film. Director Kimiai ‘s luck turned with the tragic story of Qeysar who tried to avenge his poor young sister who was raped, got pregnant, and eventually killed herself. On top of that, in the following years Kimiai, thanks to his film, also determined the way women take part in the cinema. However, this image was not that positive as women were being commoditized and perceived as malicious.

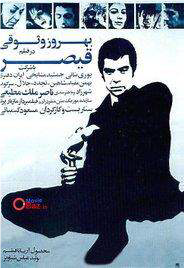

Masud Kimiai - Qeysar (1969)

In addition, Qeysar represented Iran’s poor neighborhoods, craftsmen, human relations with their realist states. It took over this tradition from its pioneers improved it and passed it to its sequents. Of course, Qeysar does not owe its importance to the storyline. In Qeysar, we witness all kinds of tragedies which we already know from the Turkish cinema. However, while presenting this tragedy, the director didn’t make any concessions from reality, not even for a minute. Also, Qeysar is not overrated and it does not overshoot itself like today’s films that earn reputation with vengeance stories such as Park Chan-Wook’s film Oldboy (Oldeboi, 2003); it rather gains appreciation for being earnest.

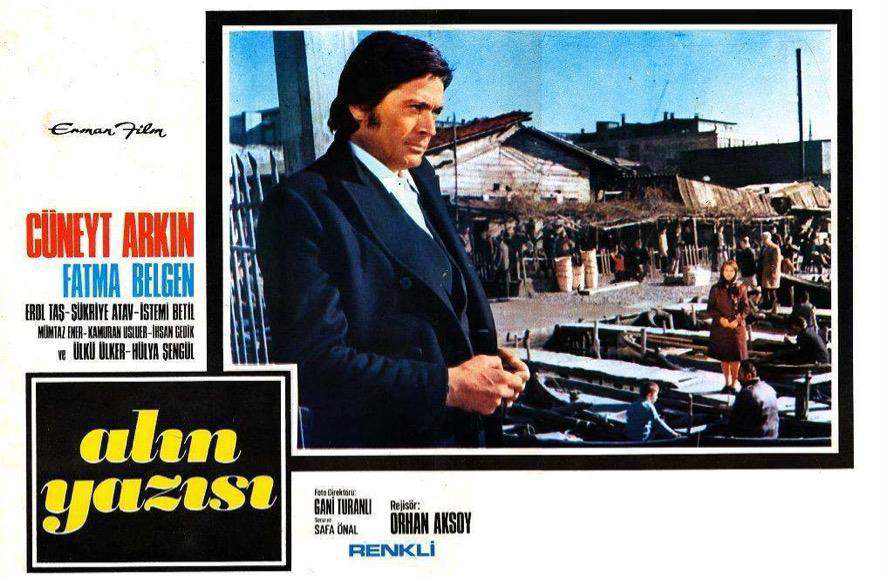

I had watched a poor quality version of Qeysar on a DVD without subtitles about three years ago. Indeed, there was no need for subtitles because the film was telling the story in its simplest possible way. Besides, the music that was heard just in the beginning of the film and that could easily be engraved in one’s mind was familiar to me. The song composed by Esfandiar Monfaredzadeh was exactly the same with the one in a film that I watched years ago, The Destiny (Alın Yazısı, Orhan Aksoy, 1972) starring Cüneyt Arkın. Only in the middle of the film it hit me that The Destiny was the adaptation of Qeysar. Today, it’s a known fact that Aksoy’s film is a direct copy of Qeysar.

Naser Malek Motiee in the poster of the film Qeysar and its spin-off film The Destiny (Alın Yazısı) featuring Erol Taş

Qeysar opens with close screenings of some tattooed men bodies accompanied by Monferadzadeh’s music. Those tattoos were the symbols representing Iranian folk art and probably their heroic epic. The tattooed men footages in this relatively long credits reveal the overall structure of the film. Yes, the film is a “revenge-themed tragic action drama” but above that it is a “man’s” film. The director who succeeds to attract the attention of the audience in the intro wastes no time in starting the story and we immediately find ourselves chasing an ambulance rapidly moving forward. Kimiai applies the steady rule “make an impressive opening and grasp the attention” from the very beginning and continues with a steady narration.

The tattoos in the opening scene of Qeysar

Ambulance is carrying the young girl who committed suicide, and her aunt and uncle accompanies her. The doctor soon notifies that the girl is dead and jeremiads of the aunt and the uncle hint what will happen next in the film: “What are we supposed to say to her brothers? What are we supposed to say to Farman, to Qeysar?” Before long, Farman, (the character played by the beloved professional actor Naser Malek Motiee who took place in some Turkish films), who heard the news appears in the corridor with his butcher apron and bowler hat which seem funny to the audience at first, but they easily get used to it. The letter the girl left behind explains everything clearly, and Farman gets angry and busts the warehouse run by the rapist and his brothers. There, while Farman was about to strangle the rapist Mansoor, his two brothers Rahim and Karim stabs Farman to death from behind.

“Qeysar! Where are you? They are killing your brother!”

Peculiarly, the lead actor’s appearance takes place almost twenty-five minutes after the opening scene. Qeysar, wretchedly, returns to his hometown with a long train ride from the town where he works. (Behrouz Vossoughi, who played his first big role here, later became one of the legendary actors of Iran.) Qeysar’s walking with a confidence while stepping on the back of his shoes and wearing them again before each fight has become a symbol of his role, and also it suits to Cüneyt Arkın very well in the film The Destiny. Of course, we are used to the artificiality of Cüneyt’s tricks but that doesn’t exist in Vossoughi’s acts. It can be understood that Vossoughi was a rough diamond till that film, but the role Qeysar suited him well.

Qeysar comes into town to see his fiancée but when he arrives he learns what has happened to his family, he then needs to make a tough decision. His genes and upbringing lead him towards revenge, whereas his affection for his fiancée holds him back. In the end, his genes prevail and he kills his three enemies; he kills Karim in a hammam, Rahim in a slaughterhouse, and Mansoor at a train station where he is also caught and killed by the police. All three murder scenes are given with long plans that hold the tension: Qeysar scans the place first, planning how to reach his target then he kills him brutally and leaves the scene in cold-blood. Sequences in these murder scenes, especially in the first two, reflect the culture excellently as if they are short documentaries: Cruel bath masseurs in the hammam, a man praying on the central platform with his peshtemal on, cloudy mirrors on the wall for those who want to shave; animals brought to the slaughterhouse, slaughter rituals, and meat distributions; the human mosaic reflecting the Iranian culture of that time in the train station. Although this film is only the second one of Kimiai, with the sequences that are full of tension, he manages to arouse the audience’s curiosity for his next movies.

Behrouz Vossoughi’s attitudes and sitting position and Arkın’s impersonation of him

Qeysar also uses sexuality bravely in a degree that was unexpected from an Iranian film. For example, young actress’ breasts can be seen in the rape scene. Also, in the night club where Qeysar went to ask for Mansoor, the women singer’s dance and clothes are striking. Actually these footages are surprising especially for today’s cinema lovers who doesn’t know those times in the Iranian cinema and who are used to see those women in hijab.

Despite of the presence of intense eroticism in the film, romantic relationships are quite conservative. Qeysar and his fiancée are alone together in some scenes yet there occurs no intimacy between them. The scene where Qeysar lays his eyes on his fiancée from afar while she prepares tea for him may be an exception, but that’s all. The women who work at the night club and who are partially from the upper class dress up and do not wear hijab, whereas those who live in poor neighborhoods dress the same as we see in today’s Iranian films.

Farman’s bowler hat which he never took off is an interesting feature in the film. It reminds us of the agha figure that is stuck between modernization and localness in the Turkish village films. As a consequence, it is not necessary for Farman’s past to be shown in the film; he is just a conservative small retailer living in a conservative town where modernization pain is deeply felt. For him, his hat is the symbol of longing for climbing the social ladder and being in limbo. In The Destiny bowler hat that Erol Taş wears seems unnatural because it only finds its meaning in Qeysar. The reason is that we got over that pain almost 50 years ago.

There are many scenes that define the social status and support the narrative of the film. In order to explain them, we need to know the Iranian society and history very well, but I can give some examples: In the rape scene, young girl studies and the name of her book is Domestic Economy; in the coffee sequence where Qeysar learns the place of his first target we see wrestler images on the wall, (director intentionally keeps the images inside the frame); in the hammam scene a man wearing peshtemal prays in the central platform (it must be a Shia tradition.); in the opening scene there are symbolic tattoos ornamented on naked men’s bodies which we have mentioned above. There are other examples like details of wall decorations in Qeysar’s home, and images of Hazrat Ali on the wall; Qeysar’s laying his eyes on his fiancée when she is preparing embers unaware of being watched (woman, man, and embers/fire; an excellent idea for romantic love eroticism that is self-censored!); the lottery ticket Qeysar buys for the next day while trying to plan his last murder in the night club; and the shoes he wore as a sign of an upcoming fight… Last but not least, it’s symbolized that murder is a man’s job and it only occurs in places where men are present (hammam, slaughterhouse, and train station)!

Some of the Iranian actors/actresses have become known and popular in Turkey especially during 70s as a result of the co-productions. For example; Reza Beyk Imanverdi (Little House/Küçük Ev, Safa Onal, 1977), İraj Ghaderi (Acı Hatıralar, Atif Yilmaz, 1977), Cihangir Gaffari (Zagor, Mehmet Aslan, 1970), Manoochehr Vossoogh (Perisan, Mehmet Dinler, 1976), Firuz (Adalet, Melih Gülgen, 1977), Humayun Tebrizyan (The Nameless Knight/Adsız Cengaver, Halit Refig, 1970), Sait Seyit (Altar, 1985), and Ali Miri (Can Pazarı, Orhan Elmas & Ertem Göreç, 1974). Also, Pouri Baneai who played Qeysar’s fiancée in Qeysar co-stars in the film Can Pazari with Kadir İnanır.

Naser Malek Motiee is one of the most beloved and renowned one of all. During his Turkish cinema (Yeşilçam) years, Naser, who plays Farman in Qeysar, played roles where he impersonated a man who first tries to avenge his loss brutally then gives up because of his compassion and soft-heart in the films Deprem (Serif Goren, 1976) and Baraj (Orhan Aksoy, 1977). Although not well known in Turkey, Behrouz Vossoughi is one of the most famous actors in Iran. Vossoughi who played in more than ninety films earned reputation in many international festivals and is honored with the Lifetime Achievement Award at the San Francisco International Film Festival in 2006. Moreover, he is one of the lead actors in the film Rhino Season (Fasle Kargadan, Bahman Ghobadi, 2012) which also became popular in Turkey.

Published in SEKANS Sinema Kültürü Dergisi, August 2017, Issue e5, pp. 84-92

Translated by Esila Sucu

This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.